While state law primarily determines how elections are conducted, federal law also sets standards that all states must follow.

At the federal level, the U.S. Constitution, federal laws, and agencies all impact state and local administration of federal elections. In each state and territory, state constitutions, laws, and regulations dictate how election administrators carry out federal election functions—from registering voters to certifying election results. State-based processes must comply with federal law. States may further delegate authority to local government to regulate election administration and make policy decisions impacting the conduct of federal elections.

This overview of federal laws related to elections is intended to provide context for election administration and is not to be construed as legal advice.

Voting Rights and Voter Registration Laws

Codified at 52 U.S.C. 10301-10314, 10501-10508, and 10701-10702

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) was passed in 1965 after Congress determined that existing federal antidiscrimination laws were not sufficient to overcome resistance by state officials to the enforcement of the 15th Amendment. Pursuant to the VRA, the Attorney General undertakes investigations and litigation throughout the United States and its territories. The VRA has been amended several times, with the most recent major amendments in the Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006.

The Voting Rights Act and Language Assistance

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) includes provisions to ensure that language-minority citizens have access to the electoral process.

Specifically, Section 203 of the VRA requires certain jurisdictions, usually counties but sometimes townships or municipalities, to provide bilingual voting materials and oral assistance. These requirements apply when specific conditions are met regarding the number and concentration of citizens who are members of a language-minority group and who are not proficient in English.

A jurisdiction must provide language assistance if more than 10,000 or over 5% of the total voting-age citizens in the jurisdiction are members of a single language-minority group and are limited-English proficient, and if the illiteracy rate of these citizens is higher than the national illiteracy rate. The U.S. Census Bureau determines which jurisdictions meet these thresholds based on census data. According to the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Justice, there are currently more than 20 languages covered under Section 203 of the VRA. Jurisdictions that fall under Section 203 are required to provide all election information, including voting materials, ballots, instructions, notices, and other written materials, in the relevant minority languages. They must also provide oral assistance in these languages.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) is responsible for enforcing these provisions. Jurisdictions found to be noncompliant may face legal action. Obligations of jurisdictions include training poll workers to assist voters in minority languages, accurately translating election materials, and publicizing the availability of language assistance. The DOJ provides guidelines and technical assistance to jurisdictions that fall under Section 203.

In summary, the language requirements under the Voting Rights Act ensure that language minority citizens can access the electoral process through bilingual election materials and assistance, primarily guided by Section 203.

The Voting Rights Act and Election Observers

Before Shelby County v. Holder invalidated the VRA’s Section 4(b) coverage formula that pertained to pre-clearance, the Attorney General could assign federal observers to voting areas it believed were at risk of discrimination. Pre-Shelby County, federal observers were appointed by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to monitor election activities and help assess compliance with federal voting rights laws.

Post-Shelby County, the DOJ can still send federal OPM observers if it obtains a court order or under a consent decree with the relevant jurisdiction. Such federal observers may be tasked with:

- Monitoring polling places to observe whether voters are being subjected to discriminatory practices;

- Reporting on the conduct of election officials and the treatment of voters;

- Observing the overall election process, including voter registration, ballot distribution, and vote counting.

In sum, the DOJ has two options to send federal observers to monitor state administration of federal elections:

- The DOJ can send OPM federal observers to jurisdictions where a relevant court order or consent decree applies; or

- The DOJ can send DOJ personnel to monitor elections with the permission of the jurisdiction.

The Voting Rights Act and Section 2

Section 2 of the VRA provides that no voting qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any state or political subdivision in a manner that results in the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group. Section 2 is a nationwide prohibition against discriminatory voting laws.

Section 2 prohibits both intentional discrimination and practices that have a discriminatory effect, even if not intended to be discriminatory. Courts use the “totality of circumstances” test to determine whether a law or practice violates Section 2. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1985). In Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the Supreme Court noted that some factors in the “totality of the circumstances” test included the size of the burden imposed by a challenged rule and the size of disparities in a rule's impact on members of different racial or ethnic groups. 594 U.S. 647 (2021). Specifically for cases related to so-called “time, place, manner” challenges, the Supreme Court identified guideposts for analysis, including whether the election process is not “equally open to participation” by a minority group “in that its members have less opportunity” than other voters to participate in the voting process and must take into account “other available means of voting.”

Section 2 serves as a basis for legal challenges against voting practices that may discriminate against minority voters. One common type of Section 2 claim is vote dilution, where electoral practices (such as redistricting plans) diminish the voting power of minority groups. States must consider the requirements of Section 2 and current case law when developing and implementing voting policies. See, e.g., Brnovich v. DNC, 594 U.S. 647. Courts may require jurisdictions to modify or abandon discriminatory laws or practices. Jurisdictions may need to provide language assistance and conduct outreach to ensure that minority voters are informed and able to participate in elections.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) monitors compliance with Section 2 and can bring lawsuits against jurisdictions that violate its provisions.

Codified at 52 U.S.C. 201501-20511

The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) outlined several requirements for voter registration, including:

- State agencies where registration must be offered,

- A national mail voter registration form; and

- Practices around list maintenance.

The law sets a national baseline for voter registration requirements that apply to federal elections. With its passage, Congress aimed to increase opportunities for citizens to register to vote or update their registration and provide a process for election officials to update voter lists and ensure they remain accurate.

The NVRA applies to all states and the District of Columbia except:

- States with no voter registration as of August 1, 1994, and have never implemented a system of voter registration thereafter (North Dakota); and

- States that permitted same-day registration as of August 1, 1994, and have never eliminated the option (Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Wyoming).

The NVRA is often referred to as the “Motor Voter Law” due to its requirement that states permit a resident to register to vote at their motor vehicle agency (often a Department of Motor Vehicles or other similar agency). States must include an application to register to vote as part of an application submitted to the motor vehicle agency (like an application for a driver’s license, a renewal, or to update an address).

The NVRA also requires state offices that provide public assistance and offices primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities to provide registration opportunities. Offices that provide services to persons with disabilities must make voter registration available at the person’s home.

States may provide registration opportunities at other government offices like schools, libraries, city and county clerk offices, and unemployment offices. And the federal government, including the Armed Forces, is directed to cooperate with states in implementing these voter registration requirements. Armed Forces recruitment offices are considered voter registration agencies.

The government office must transmit the voter registration form to the state election official within 10 days of receipt. If the registration is received within five days of the voter registration deadline, the window to deliver the registration to the state election official is shortened to within five days.

The NVRA requires the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) to create and maintain a mail voter registration form that all states must accept to register a voter or update their address. In general, the form can only require information needed to allow a state to assess the eligibility of the registrant. It must include:

- A list of eligibility requirements;

- An attestation to meeting the eligibility requirements; and

- A signature block.

The form cannot include a notary requirement or any other formal authentication.

States can also create a state voter registration form and make it generally available.

If a voter uses the national mail voter registration form to register, they may be required to vote in person if:

- They have not previously voted in the jurisdiction where they registered; and

- They must provide a specified form of identification unless they provided identification when they registered.

Note that there are exceptions to the above voting in-person requirements for UOCAVA voters and voters with accessibility needs under the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act.

States must accept voter registrations up to at least 30 days prior to an election, though they may choose to set a registration deadline closer to election day. When a registration is received, election officials must notify the voter whether the form was accepted or rejected.

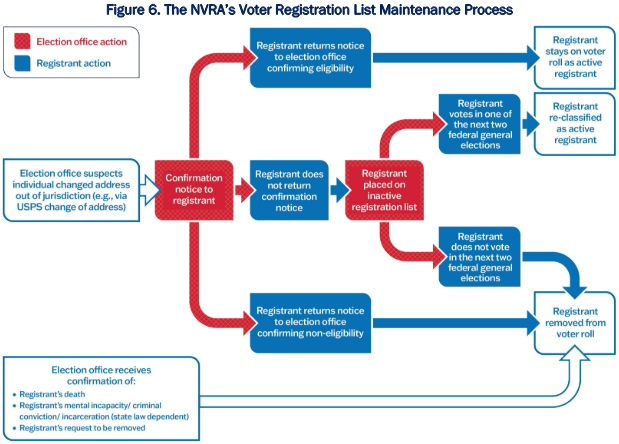

The NVRA requires states to implement a uniform and nondiscriminatory voter list maintenance program. The purpose of the program is to keep voter lists up to date and provide a process to make sure that voters are eligible to vote at their registered addresses. Maintaining accurate voter lists can have downstream effects like reducing provisional ballot use and providing more accurate voter numbers for planning and budgeting purposes. The program must also comply with the Voting Rights Act, remove voters who have died or moved out of the jurisdiction, and cannot remove a voter solely due to failure to vote. Generally, states may remove a voter from the registration list if the voter:

- Requests removal;

- Is convicted of a criminal offense or is found mentally incapacitated, if state law permits; or

- Fails to respond to a change-of-address notification.

General list maintenance programs resulting in the removal of registrations must be suspended no later than 90 days before a primary or general federal election. However, individual removals based on death, request of the voter, or criminal or mental incapacity may continue. Also, the merger of duplicate registrations based on a move or multiple registrations is generally permitted. The removal of non-citizens inside the 90 day period is the subject of current litigation.

For a visual representation of this process, view the diagram above.

Codified at 52 U.S.C. 20901-21145

The Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) established the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) and set new baseline standards for states in several areas of election administration.

HAVA and the EAC

HAVA mandates that EAC test and certify voting equipment, maintain the National Voter Registration form, and administer a national clearinghouse on elections, including shared practices, information for voters, and other resources to improve elections. Section 803 of HAVA transferred the functions of the FEC's National Clearinghouse on Election Administration to the Election Assistance Commission.

HAVA states that the Commission shall serve as a national clearinghouse and resource for the compilation of information and review of procedures with respect to the administration of Federal elections. EAC shall establish and maintain a clearinghouse of information available to the public on:

- Voluntary guidance adopted by EAC regarding the following HAVA mandates: voting system standards, provisional voting and voting information requirements, computerized statewide voter registration list requirements, and requirements for voters who register by mail.

- Information on the experiences of state and local governments in implementing the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines and in operating voting systems in general.

- Information relating to the testing, certification, decertification, and recertification of voting system hardware and software.

- Information and training on the management of HAVA payments and grants.

- The Help America Vote College Program.

- EAC’s responsibilities under the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) which include the development and maintenance of the national voter registration form and biennial reports to Congress on the impact of NVRA on the administration of federal elections.

- Studies regarding election administration issues and other activities to promote the effective administration of federal elections.

- Compilation of federal and state laws and procedures regarding election administration and voting.

HAVA and Voting Systems

In passing HAVA, Congress (1) provided funding to states for the replacement of lever and punch card voting systems; (2) established several baseline requirements for new voting systems; and (3) tasked the EAC with adopting voluntary voting system guidelines.

First, voting systems must allow all voters, including voters with disabilities, to cast their ballots privately and independently. This means letting voters verify their selections and change or correct any selections before casting their ballot. Voters must also be issued a replacement ballot to make corrections, if needed.

The system must notify a voter if they’ve made too many selections in a contest, often referred to as overvoting, while maintaining voter privacy. The notification must explain the effect of overvoting and provide the voter an opportunity to correct the issue.

For jurisdictions using paper ballots or a central count system (including one for mail ballots), election officials must provide voter education on the voting system, the effect of overvoting, and written instructions on how to correct an overvote, including the use of a replacement ballot.

Voting systems must produce an auditable, permanent paper record of ballots cast that must be made available for a recount, if needed. Voters must be able to change or correct their ballot before the system produces the permanent paper record.

Voters with disabilities must have the same opportunity to cast a private and independent ballot while using the voting system. Each polling location must have at least one accessible voting machine.

Accessibility requirements also include language accessibility. Voting systems must support alternative languages consistent with Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act.

HAVA and Provisional Ballots

HAVA includes 3 main requirements for provisional voting:

- Voters must be offered a provisional ballot;

- Election officials must count eligible provisional ballots; and

- Election officials must provide a free access system with information on whether a provisional ballot is counted.

1 – Offering Provisional Ballots

If a voter arrives at a voting location to vote in a federal election and says they are registered to vote but do not appear on the list of eligible voters, or a poll worker asserts they are not eligible, they must be offered a provisional ballot. To cast a provisional ballot, the voter must sign a written affirmation that they (1) are registered to vote in the jurisdiction and (2) are eligible to vote in the election.

Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Wyoming are exempt from the provisional voting requirement because they offered, and continue to offer, same-day voter registration at the time HAVA passed. North Dakota is also exempt because it does not require voter registration.

2 – Counting Provisional Ballots

The relevant state or local election official must review each signed affirmation and provisional ballot to determine whether the voter was eligible to vote under state law. If so, the provisional ballot must be counted.

3 – Free Access System

State or local election officials must provide a toll-free phone number or website that voters who cast a provisional ballot can use to determine whether their ballot counted and, if not, why. When someone casts a provisional ballot, poll workers must provide written information on the free access system.

Additionally, if a court extends the time to vote in a federal election, voters must vote provisionally during the extended time. For example, if polls normally close at 7:00 p.m. on election day but a court extends voting until 8:00 p.m. due to significant issues in a location, voters who vote between 7:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. should vote provisionally.

Provisional ballots voted due to the court order must be kept separate from all other provisional ballots. A court will determine whether these ballots are ultimately counted.

HAVA and Voter Registration

HAVA includes several requirements that contribute to the accuracy of voter registration lists. Congress recognized the issues caused by decentralized voter registration lists within states and the potential opportunity to verify voters’ identities using other statewide databases.

HAVA’s passage marked the first time states were required to implement “a single, uniform, official, centralized, interactive computerized statewide voter registration list” to be maintained and administered at the state level. Specifically, the statewide list has to:

- Include the name and registration information for every legally registered voter in the state;

- Include a unique identifier for each voter on the list;

- Provide immediate access to local election officials;

- Allow local election officials to electronically enter information at the time they receive it;

- Coordinate with other state agency databases; and

- Serve as the official voter registration list for federal elections.

Only North Dakota is exempt from the statewide voter list requirement, as it did not require voter registration when HAVA passed and has not implemented voter registration since.

HAVA reinforces the ongoing accuracy of the statewide database by requiring election officials to perform regular list maintenance in accordance with the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA). Maintenance required under HAVA includes coordinating the statewide voter registration database with state agency records on felony convictions, as required by state law, and deaths.

A state’s list maintenance process must make sure that (1) the name of each registered voter is included in the statewide list, (2) only voters who are not registered or are ineligible to vote are removed, and (3) duplicate names are eliminated. States are responsible for accurate and regular maintenance of the system, which includes making reasonable efforts to remove ineligible registrants consistent with the NVRA and implementing safeguards to make sure eligible voters are not removed by mistake.

Election officials are also responsible for the security of the system and preventing unauthorized access.

Generally, HAVA requires registrants to include a driver’s license number or the last four digits of their social security number when registering to vote in federal elections. If the registrant does not have either number, then the state must assign them a number to be used for their identification. It is up to the state to determine whether the information provided by the registrant is sufficient to meet this identification requirement under state law. The EAC has provided voluntary guidance to states on how such verification can occur.

Unless registrants are permitted to use full social security numbers to register, states must also enter into agreements with the state’s motor vehicle authority. The agreement must allow the state to verify information in the statewide voter list with information in the motor vehicles database. These provisions provide a method of matching registrants’ social security or driver’s license numbers.

HAVA and Voter Information

Election officials post information in voting locations during federal elections. HAVA requires the posting of:

- Sample ballots;

- Date of the election and the hours the voting location is open;

- Instructions on how to vote (including casting a vote and voting provisionally);

- Instructions for mail-in registrants and first-time voters;

- Information on voting rights established by federal and state law (including the right to a provisional ballot and how to contact appropriate officials if rights have allegedly been violated); and

- Information on federal and state laws prohibiting fraud and misrepresentation.

Retention and Preservation of Election Materials

Enacted at the same time as the Civil Rights Act of 1960, though not part of the act, was the statute that is today codified at 52 U.S.C. 20701. That federal law requires election officials to keep records relating to any “act requisite to voting” in a federal election for 22 months.

For more information on Voting Rights and Voter Registration Laws:

Accessibility Laws

Codified at 42 U.S.C. 4151-4156

The law requires that buildings or facilities that were designed, built, or altered with federal dollars or leased by federal agencies after August 12, 1968, be accessible. Facilities that predate the law generally are not covered, but alterations or leases undertaken after the law took effect can trigger coverage. The law does not cover the activities within the facility.

The law covers a wide range of facilities, including U.S. post offices, Veterans Affairs medical facilities, national parks, Social Security Administration offices, federal office buildings, U.S. courthouses, and federal prisons. It also applies to non-government facilities that have received federal funding, such as certain schools, public housing, and mass transit systems.

The United States Access Board maintains accessibility guidelines under the ABA and enforces the standards through the investigation of complaints.

The ABA standards can serve as guidelines in helping determine how to make non-federally funded buildings more accessible, even if they are not directly applicable. For example, the ABA standards can help a jurisdiction estimate the disabled population it expects to accommodate in a facility and what attendant accommodations (parking spaces, bathroom stalls) are needed in that facility.

Codified at 52 U.S.C. 20101-20107

The Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984 generally requires polling places across the United States to be physically accessible to people with disabilities for federal elections. If no accessible location is available, then voters must be provided an alternate means of voting on Election Day. The law is enforced by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The law also requires states to provide accessibility to registration and voting aids for disabled persons, ballots printed in large print font, and access to aids, including telecommunication devices for the deaf. A state cannot require a medical certification or doctor documentation to verify a disability. In 2015, the law was amended to allow anyone who is physically disabled or over the age of 70 to move to the front of the line at a polling place.

Codified at 42 U.S.C. 12101-12213

The ADA requires state and local governments and their election officials to ensure that people with disabilities have a full and equal opportunity to vote in all elections. This includes federal, state, and local elections. And it includes all parts of voting, such as voter registration, voting locations, and voting processes, whether in-person on election day or during early voting, or when voting by mail.

For voter registration, the process must be accessible to people with disabilities – a state or local government cannot categorically disqualify people with disabilities from voting because of their disability.

Polling places must be accessible to voters with disabilities. The ADA’s regulations and Standards for Accessible Design define what makes a polling place accessible. This includes regulations related to parking, sidewalk cuts for wheelchair accessibility, ramps, width of hallways, doorknobs and door openings, and crowding of voting spaces. Election officials must provide reasonable accommodations, including permitting voters to sit down (instead of standing in a long line), allowing voters to bring their service animal into a polling place, permitting voters to have a companion with them in the voting booth if they need assistance, or modifying other voting policies and practices when necessary to avoid discrimination.

The ADA also covers early voting processes. For example, if a jurisdiction uses drop boxes, those boxes must accommodate voters with disabilities, or there must be an alternative to casting an early ballot.

For more information on voting and accessibility:

- U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC): Voting Accessibility

- U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC): Accessible Elections - Information for Election Officials

- U.S. Department of Justice - Civil Rights Division: Voting and Polling Places

- U.S. Department of Justice - Civil Rights Division: ADA Checklist for Polling Places

- U.S. Access Board

Laws Impacting Military and Overseas Voters

Codified at 52 U.S.C. 20301-20311

The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) of 1986 protects the voting rights of members of the Uniformed Services (on active duty), members of the Merchant Marine and their eligible dependents, Commissioned Corps of the Public Health Service, Commissioned Corps of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and U.S. citizens residing outside the U.S. UOCAVA requires that the states and territories allow certain groups of citizens to register to vote, as well as request and cast absentee ballots in elections for federal offices. In addition, most states and territories have their own laws allowing citizens covered by UOCAVA to register and vote absentee in state and local elections as well.

UOCAVA requires the creation of a Federal Post Card Application that qualified service members and overseas citizens can use to both register and request an absentee ballot at the same time. Additionally, UOCAVA requires that the states accept a “backup” Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (the “FWAB”) for federal offices. The FWAB may be used by voters covered by the act who made a timely application for their absentee ballot but have not received it in a timely manner.

Additionally, under the provisions of HAVA, the EAC gathers information on UOCAVA voters following every federal general election; this information is gathered as part of the biannual EAVS survey and is reported in the year following the election. (See Chapter 4 of the 2022 Report, here).

The MOVE Act amended UOCAVA, changing certain voter registration and absentee ballot procedures for federal elections. MOVE requires states to allow UOCAVA voters to request and receive voter registration and absentee ballot applications by electronic transmission and to establish electronic transmission options for delivery of blank absentee ballots to UOCAVA voters. MOVE requires election officials to transmit absentee ballots to UOCAVA voters no later than 45 days before an election for federal office. The act requires states to accept otherwise valid UOCAVA voter registration applications, absentee ballot applications, voted ballots, or FWABs without regard to notarization, paper type, or envelope type. States also must permit UOCAVA voters to track the receipt of their absentee ballot through a free access system. Both UOCAVA and MOVE are administered largely by the Department of Defense and specifically the Federal Voting Assistance Program.

For more information on UOCAVA and MOVE, check out the following resources:

- U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) - UOCAVA

- U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) – Military and Overseas Voting

- Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP)

- U.S. Department of Defense - You Can Vote From Anywhere

- U.S. Department of State - Absentee Voting Information for U.S. Citizens Abroad

Other Federal Laws that Impact Elections

Codified at 2 U.S.C. 8(b)

The Constitution explicitly outlines that the executive of a state (often the governor) has the authority to appoint a Senator if a vacancy arises in the middle of a Senator’s term. However, members of the House of Representatives must be replaced via election. In light of concerns related to a “mass vacancy” event following the events of September 11, 2001, Congress passed a law in 2005 outlining specific requirements related to special elections if 100 or more members of the House are simultaneously unable to fill their terms. This law is known as the Continuity in Representation Act of 2005 and is codified at 2 U.S.C. Sec. 8(b). The law requires that, after the Speaker of the House announces such a mass vacancy exists, a special election is held within 49 days, unless there is an already scheduled election for the seat within 75 days of the declaration. It requires nominations for candidates to be made within 10 days of the declaration, or that candidates may be selected by “any other method” chosen by the state (including primaries), if such method does not interfere with the 49-day deadline. The law also requires absentee ballots for UOCAVA voters to be transmitted within 15 days of the vacancy declaration, and that election officials accept a ballot cast by a UOCAVA voter within 45 days of its initial transmission to that voter. The law further provides for expedited judicial review and that no other federal voting laws — including the VRA, ADA, UOCAVA, NVRA, and HAVA — are superseded.